Mr. Barnes got me my first job in M.H.Gill & Sons, Printers, Publishers and Ecclessticial Art Metal Works at 56 Upper O’Connell Street Dublin.

It was the summer of 1959 and I was 14 years of age.

Mr. Barnes or Ted as he was known to his peers, was an English Catholic who came to Ireland after World War II. He was a friend of my aunt Bridie. And he was a great friend and mentor to me in Gill’s.

While the Gills shop fronted onto O’Connell Street, the workshops were in Moore Lane at the back of the shop.

The printing activity took place directly behind the shop while the building that housed the foundry, the carpentry & picture framing workshops, plus the silver shop was a little further down the lane from the printers. Across the lane was the brass shop that employed about thirty craftsmen and women.

The brass shop manufactured altar railings, altar candlesticks, tabernacles, sanctuary lamps, thuribles for incense and candle shrine holders and a host of other liturgical articles.

I was based in the silver shop and swept the floors first thing every morning. My next job was to get the men in both the brass shop and silver shop their cakes and cigarettes and whatever else they needed. When this was done all of us who worked in the silvershop knelt down and said a decade of the rosary. After we said the rosary I made the tea for our 10 o’clock break.

The silver shop employed four silversmiths and an apprentice, a chaser, a polisher and a silver/ gold plater. In the small office attached to the workshop worked Mr. Barnes and Mary Cleary.

Mary was a burnisher, her job entailed burnishing the gold plating on the sacred vessels with steel and agate tools and a soapy water solution. This made the gold gleam and also helped to give the gilding the capacity to stand up to the wear and tear that the liturgical vessels would be subjected to. Her father was the foreman of the silver shop and her brother John was also one of the silversmiths. Every item made in the silver shop was formed by hand raising, which means it was hammered up from sheet.

The silvershop produced altar plate for use in the sacramental life of the Catholic Church. They included chalices for celebrating the Eucharist and cibiourms and patens for the distribution of Holy Communion. Monstrance’s for the exposition of the Blessed Sacrament in Benediction. Also pyxes for carrying the holy communion and stocks for the holy oils used for anointing the sick and dying and other blessings.

The repertoire of motifs in use in the workshop that were either engraved or chased on the altar plate included; Celtic interlacing, the Wheat and Vine, the Pelican feeding her young by piercing her breast and feeding them her blood, the Lamb, the PAX sign, the Alpha & Omega, the IHS and of course the Cross in all its manifestations. All these symbols were akin to musical notes and were used in many different combinations to produce different designs to embellish the chalices and Monstrance’s and other sacred vessels.

At this time in Ireland, and especially Dublin, a lot of new churches were being built to serve the new parishes growing up in the expanding suburbs.

Moore Lane, Dublin Gills silver shop was located on the right.

The architects who designed the churches also esigned the church furnishings including the litdurgical vessels.

Gills were famous for its Papal DeBurgo Chalice that was presented to Pope Pius XII in 1950 by Sean O’Kelly, President of Ireland. It was in the style of the famous DeBurgo-O’Malley chalice made in 1494. The liner was chased with a mixture of pure Celtic peltra motifs and interlacing. The rest of the chalice was chased all over with the combinations of designs mentioned above. It was fabricated out of 18ct gold. Gills also made a bronze Monstrance for the newly opened Telefis Eireann (Irish National Television) for the televised Benediction program. It was in the shape of a Celtic cross with flat chased interlacing covering the four surfaces of the cross. It was made of bronze and not highly polished because they did not want too much reflection from the television studio lights.

When proposals for new jobs arrived in the workshop, the foreman, George Cleary, would gather the other silversmiths, the polisher, Christy Edwards, and the chaser Bobby McGrath. This conference took place at a sturdy table where the drawings for all new work were first evaluated for pricing and to examine the feasibility of making

the article. I can still see and hear in my mind the great discussions that took place at the table. One comment in particular still sticks in my mind. “Ah sure, you could not make this,. These architects know nothing about silversmithing.” This table was also the place where every item made in the workshop was given the once over to make sure everything was as it was supposed to be. The table was perfectly level and a plum bob hung from the ceiling to make sure the article was straight.

It was also my job to bring and collect work from the out workers and specialist craftsmen and women scattered across the city. There were three different engravers used by Gills. Also a jewel case maker by the name of Jack Barclay, who custom made cases for the chalices,ciboriums and monstrance’s I brought to him. I loved going over to his workshop, where he would tell me to sit down and rest while he took measurements of the item. Then he would tell me stories of his time in the First World War, when he served with the Black Watch, a Scottish regiment. He also told me stories from the Táin and of CúChulainn’s amorous adventures with the opposite sex which he said they did not mention in the schools we all went to. The Dublin Assay Office was another port of call where I brought the silverware over in a green baize sack. The Assay Office is where all items of silver and gold manufactured in Ireland must by law be tested and hallmarked before they can be offered for sale.

We would get the odd order for a Bishop’s Pectoral cross which would be studded with jewels and sometimes other articles could be studded with jewels. These articles would be sent out to John Colgan the stone setter. The Pectoral Cross was the nearest we came to making jewellery. As at that time in the precious metal trade silversmiths did not make jewellery.

A jewellery maker would have been referred to as a goldsmith.

Although silversmiths also worked in gold, the term goldsmith means in this sense someone who makes small work.

I helped around all the workshops and in the office. Mr. Barnes would get me to make new drawings of the various articles that were made in the workshop.

I would pumice the brass hammered patens in the polishing shop to get the marks and scratches out, and scratch brush newly plated items.

John Wills was the picture framer. I would touch up any of the frames that were damaged in the making, using oil paints.

I was good at this. John was the first man I met who had ever been to Spain. He would regale me in words and deeds with dramas about the bull fighters and the flamenco dancers he saw there.

Billy Dunne was the carpenter and the odd time I would go out on a job with him.

Billy was one of the most intelligent if not the most intelligent man I have met in my life. He was, as they say, “out in 16” (he took part in the 1916 Rising as a young messenger).

He was a bagpiper and a fluent Irish speaker. Before Google, everybody from high up to low down, who had an unanswered question went to Billy for the answer, which he duly provided. His time sheets were works of art. He had a beautiful copperplate hand. His one failing, and it has been the failing of many a good man and woman, was the drink. Beside Gills was a store house that held barrels of ale belonging to the Bass Carrington Brewery. Now the odd time when Billy was tempted to go in for a quick one, he would invariably come out the worst for the wear. As far as I can recollect he was met with forbearance and tact from all concerned.

When I was sixteen I was offered an apprenticeship as a chaser. Bobby McGrath was the chaser in Gill’s at this time.

I jumped at the chance. My first job was chasing the tassels for the bottom of a sanctuary lamp.

These sanctuary lamps were about 16” in diameter and had simple interlaced panels chased on them.When I started my apprenticeship Gills paid for my tuition at the College of art where I went at night. I was also allowed nay encouraged to make copies of pages from the Book of Kells and try to create original metalwork in the style of Irelands Golden Age. Bobby left Gills to join the signals corps of the British Army and David Hickey the chaser at Gills before McGrath came back from England to work for the firm again, for a short time.

I worked away and at night, when not attending the Art School, I made oil paintings from post cards for a man called Joe Brennan who provided me with the cards. Joe was one of the salesmen in Gills shop and he paid me a pound for each one. It was not chickenfeed. I also loved to visit the museums and galleries. At this time the National Museum of Ireland had plaster cast replicas of the High Crosses on display in the foyer with pictures of other heritage sites around the walls I used to cycle to some of sites that were near such as Clondalkin where there is a Round Tower and Swords, where I live now,. Back then it was exotic and far away from where I lived in Killester, relatively speaking. I visited Blackrock, where there are the remains of an ancient small cross with a face carved on it and St Douloughs Church and cross, the shape of which is echoed by the Penal Crosses which was also the inspiration for one of my earliest pieces of jewellery. I even cycled all the way to Glendalough in County Wicklow, where I spent the night in a youth hostel.

Moore Lane, Dublin

Gills silver shop was located on the right.

The silversmiths shop at Alwright and Marshall. 1980. The chasers worked at the bench in the foreground. Photo : Gerry Brady, National Folklore Collection,UCD.

Alwright and Marshall

14 Fade Street, Dublin as it appears in 2013.

The other silversmithing and Ecclesiastical art metal working firms operating in Dublin at this time were Gunning’s, that was by far the biggest producer of sacred metalwork and they exported all over the world. One of their most famous pieces is

The silversmiths shop at Alwright and Marshall. 1980. The chasers worked at the bench in the foreground. Photo by Gerry Brady, National Folklore Collection, University College Dublin

had Matt Stanton on Dawson Street who made the iconic Sam Maguire Cup for Hopkins & Hopkins. And up the end of Harcourt Street was the Jewellery and Metal Company. This was the stunning Fatima Monstrance. Smyths, of

Wicklow Street, was another firm. You also not considered a real silversmithing firm by the men I worked with.

I left Gills to go to work in Alwright & Marshal Silversmiths in Fade Street when I was eighteen. Alwrights as we called it was a lot different from Gills in that it concentrated on domestic silverware as opposed to Ecclessticial ware. Even though the first thing I was shown when I went there were the patterns the firm made for their replica of the Cross of Cong. They did make the odd chalice as well. A feature of all these firmswas that the craftsmen took an interest and great pride in the work that was produced by their firm. Alwrights was also different from Gills in the way the workwas fabricated, they had spinners. A spinner forced a metal disk over a chuck on a lath to produce a form a whole lot quicker than one raised by hand

Alwrights started out as Wakley & Wheeler, an English firm. After Irish independence in 1922 they decided not to stay in the new state and in 1929 the owners left and sold the business to two of the workers , Johnny Alwright, a silversmith and freedom fighter as I was informed, and JockMarshall a Scots Presbyterian and a chaser. An unlikely partnership but a very successful one. When I arrived Johnny had departed to his eternal reward. His wife Elizabeth, or Lizzie as she was known to all when she was not in earshot, was theboss and ran the place, ably assisted by Tony Marshall, the foreman silversmith and another greatfriend to me.

The building we worked in was a part of the South City Markets complex, it was three stories high. The spinners were on the ground floor, the polishing & plating on the next floor, Lizzie’s office and the silver shop on the third floor. The silver shop was over an arcade and entrance to a meat factory, with a pillar holding up the entrance. This pillar would regularly get a belt by a lorry delivering produce to the factory. Our workshop would rumble and shake. Working in the silver workshop was like working in a cathedral as from floor to ceiling it was about 24 feet high and one wall had Gothic style windows from wall to wall and from bench to ceiling.

Jock took me under his wing and gave me my head when I had not got a chasing job that was needed .When this happened he would tell me to cut up a piece of brass and chase a shield, usually with a Celtic or Shamrock design. I was given the freedom to decorate it as I saw fit. We had a pile of these shields a foot or so high of various shapes and sizes. When the workshop got the call for a sports trophy, one of the silversmiths rooted around in this pile until he found something that suited. It was the custom in Alwrights to take a plaster cast of all jobs we chased.

A lot of the articles produced in Alwrights were decorated with Celtic design. These included replicas of the Ardagh Chalice in many forms, including tea sets.

The Dunvegan tea set was based on a medieval Maguire chalice that ended up in Dunvegan Castle on the Isle of Skye Scotland. The Carroll tea set was also chased with interlacing. Salvers with interlaced borders wereanother popular item. As I browse the antique shops today I can see lots of silver plate that was

made in Alwright & Marshalls. If you see something with the “Weirs” or “Wests” hallmark its odds on it was made in Alwrights.

Joe Dalton the polisher and plater related to me the story of how one of the young West’s sons was apprenticed to Jock as a chaser.

He was a bit of a playboy and tragically was killed driving a fast sports car. Weirs also had some kind of special relationship with Alwrights.

Sydney Booth, Weirs’ representive was around so often he was like a member of the staff. Jimmy Martin and Tommy Sharkey were two other chasers I worked alongside in Alwrights.

Jimmy was a theatre buff,and would regularly recite Molly Bloom’s soliloquy from Ulysses.

Tommy was renowned for being able to write the Lord’s Prayer with a pencil on the back of a postage stamp.

Tony Marshall once told me that in the old days the chasers worked on the ground floor and there was beer on draft in the workshop to make it attractive for the chasers to stay in the workshop.

In 1965 the Second Vatican Council concluded. It was to usher in sweeping changes to the liturgy that changed the architecture of the churches as well as changing the rubics regarding the composition of materials that could be used for scared vessels. Prior to Vatican 11 the cup of the chalice had to be made of silver and gilt inside. After the Vatican II a chalice could be made of ceramics or non-precious metal. By 1968 there were no silversmiths working in Gill’s, Gunning’s, Smyth’s, or for that matter Stanton’s. Gunnings had transformed itself into a company called Royal Irish Silver and they movedfrom Fleet

Street, in what is now the fashionable Temple Bar area of Dublin, out to the Glasnevin Industrial Estate. I left Alwrights and went to work there in 1969. At one stage there were about 120 employed there. There were six of us chasers and an apprentice working in our own wooden building.

On a Monday morning it was the custom of the company to burst into song with.

“What will we do with the drunken chaser?

What will we do with the drunken chaser?

Put him in the pitch pot till he’s sober

Put him in the pitch pot till he’s sober

Ear-lie in the morning.”

The money was great in Royal Irish and the work was interesting. But I could not in all honesty say it was my favorite place to work. As far as I can remember we made very little Celtic style silver plate with the exception of Celtic salvers, it was mostly reproductions of Georgian silver. The Dairy Maid Tea service was the most popular and bestselling piece.

All the people who worked in the silver trade at that time were members of The National Union of Gold Silver & Allied Trades, an English trade union. Such were the contradictions

in Ireland at that time. The trade was organized along clear lines of demarcation with a silversmith confining himself to what was considered a silversmiths work.

For example, he would not polish or chase, and likewise a chaser would not polish or do silversmithing.

It made some sense because a lot of the skills were very specialized.

Workbench at Alwright and Marshall 1980. Photo by BrónaNicAmhlaoibh,

National Folklore Collection, University College Dublin.

Silver trophy made by Alwright and Marshall.

Dublin hallmarks for 1963.

Silver Salver with Celtic border made at Royal Irish Silver,

Dublin hallmarks 1972

I left Royal Irish after two years and went to work in Irish Silver Ltd., which was situated off Meath Street, in an area known as the Liberties of Dublin. The workshop was an eighteenth century converted Quaker Meeting House building. The men agreed that I could move across the lines of demarcation because there was not enough chasing to keep a chaser employed for forty hours a week. I am very grateful to them for that. We made a fair number of Celtic style articles of silver plate and the signature Celtic piece would have been a rose bowl with pierced Celtic zoomorphic cover.

Irish Silver’s proximity to St. Patrick’s Cathedral gave me the opportunity to visit the cathedral on my lunch break. I loved looking at and studying the many memorials that adorned the

walls.

There were a number of beautifully engraved brass plaques featuring Celtic interlacing.

While working in Irish Silver the work was short and we were reduced to a three day work week. I had started making Jewellery purely by accident. A friend had asked me to make him a Celtic cross and between one thing and another I started to get more requests for Jewellery. I had no formal training in Jewellery making, apart from my chasing and repousse skills and the silversmithing skills I picked up in Irish Silver. I was well able to saw pierce because as a child I used to do fretwork with the encouragement of my father who was a joiner.

From the time I started working I have always done what we call “nixers”, or working in my spare time for other companies. In Gills I had my paintings. When I worked in Alwrights, Paddy Malone, one of the silversmiths, introduced me to Lionel Mitchell, an antique dealer specializing in brass artifacts of every variety. I helped him restore the decorated brass surrounds on Georgian fire places and the brass dials on grandfather clocks, as well as well as anything that was needed. Incidentally Lionel did not encourage me to make jewellery; he actually discouraged me, telling me “not to prostitute myself”. He thought it would better for me to concentrate on chasing.

But when did I ever listen to anyone?

In 1978 this all resulted in me deciding to go out on my own and set up my own workshop doing what I knew best. Contract chasing and repousse work for the trade and making jewellery using the Celtic designs motifs I knew and loved. At this time I had been married to Mary for the last seven years and we had our two children Gráinne& Ciarán. My work was our only source of income. In 1979 I exhibited my work at the National Crafts Trade Fair, which is now known as “Showcase”. The trade fair was held in the Royal Dublin Society exhibition hall in Ballsbridge, Dublin. When I started to show there, Pat Flood was the only other jeweler showing Celtic jewellery. Pat had a retail outlet in the Powerscourt Town House shopping centre in the city center.

I sold well at this fair. In Ireland in the nineteen eighties gold & silver Celtic Jewellery was considered high fashion and was bought by the great and the good.

Over the years I got great orders at this fair for my Celtic jewellery, including a substantial one in the 1980s from Mervyn's, a department store in San Francisco.

Later in the 1990s I had a terrific order from the Discovery Channel. I am delighted to report that it is becoming very fashionable again. That said, I have always had a market for my Celtic jewellery.

I was delighted to reestablish contact with Alwright & Marshals and to once again do their chasing. One of the jobs that gave me great pleasure was a Dish Ring (a particularly Irish form of silverware) I chased to celebrate Tony Marshal’s fifty years of service with the firm.

George Bellew was another silversmithing firm I did chasing for. One of these jobs was what, a few of us referred to as, “Sons of Sam”. These were miniature Sam Maguire Cups and I could not count the number made. I made Celtic design patterns for embellishing book covers and the Rivers of Ireland heads based on figure sculptures from Dublin’s Custom House on the river Liffey, that were used for spoon handles.

Basil Clancy’s Ogham Crafts was also another firm I worked for.

I particularly remember the whiskey measures and bookmarks I chased with” Man Bites Dog” logo.

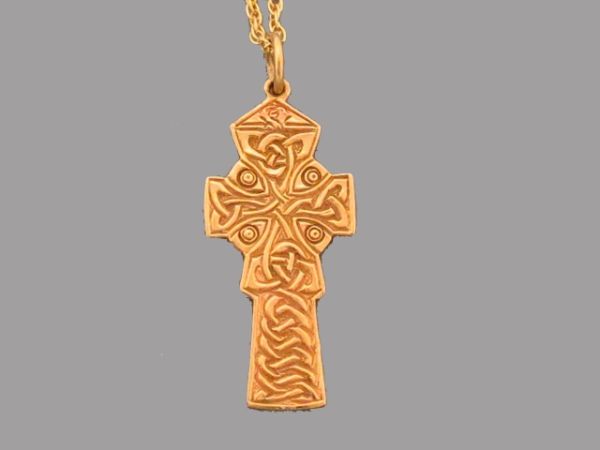

Gold cross, Aidan Breen 1980.

Gift to his daughter Gráinne.

Letter “D” from the Book of Kells, silver brooch.

Aidan Breen 1980s.

Five Bird Necklace,Aidan Breen

Based on the birds on the back of the hoop of the Tara Brooch.

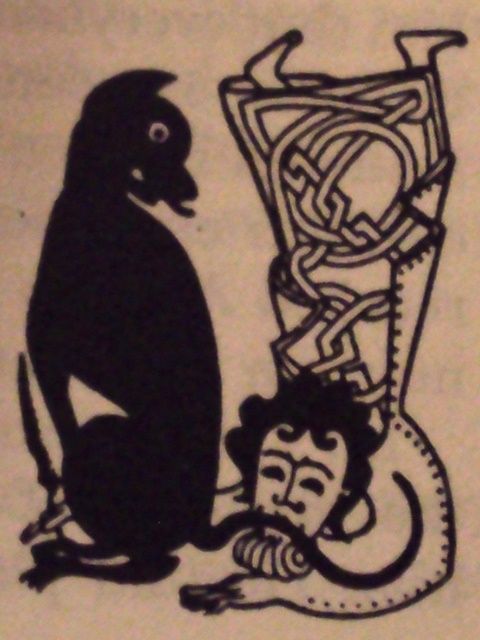

This was a design showing an interlaced man biting a dog that decorated Donal Foleys humorous column that ran in the Irish Times from 1971 to 1981.

These was sold through the Irish Times General Services, an adjunct to the Irish Times newspaper. At this time they also sold my jewellery and silver boxes.

The silverboxes were inspired by the sculptured stones from the Irish country side that ranged from the Stone Age to the Early Medieval period.

Jim Byrne was another a man I did chasing and pattern making for. One pattern that sticks out in my mind was a chased portrait of P.H.Pearse, the leader of the 1916 Rising. I also chased strawberry dishes with scenes of Dublin for him. Jim commissioned me to make an exact replica of theGlenasheen Collar. Not in gold, but in copper that was gilded. He had his shop on Dawson Street back then. He is now in South Anne St.

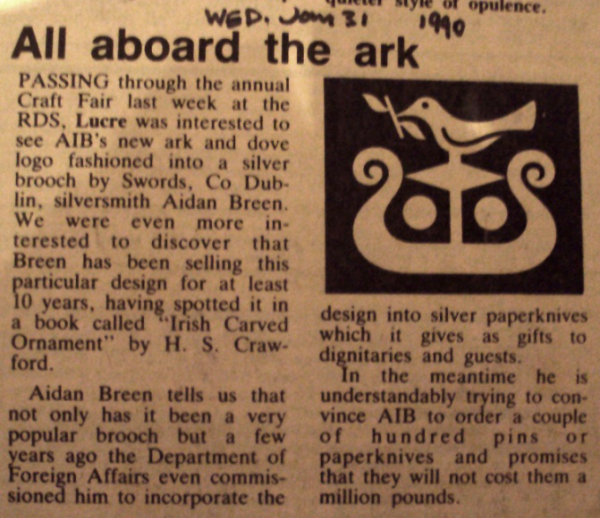

One of my most popular pieces of jewellery was Noah’s Ark based on a design from a High Cross at Killary Co. Meath. It featured a stylized boat, the ark with two faces peeping out and the dove of peace perched on top with the olive branch. I made it in brooches, pendants, and paperknives. The paperknives I sold to the Dept. of Foreign Affairs for use as gifts. I made a large one in copper for the Glencree Peace and Reconciliation Center as a wall hanging. The piece was very popular because of its association with peace much sought in Ireland at that time because of turmoil created by the Provisional IRA’s campaign of terror. This all changed when the now disgraced Allied Irish Bank paid a small fortune to a British company to design a new logo which, guess what, came up with a variation of the design I had been using. I got in touch with them and explained my connection with the design, as a sop they ordered about a dozen paperknives. But as a piece of jewellery that was the end of that. AIB ruined the design for me, but about twenty eight years later, they, along with a number of other banks, ruined this proud country.

My good friends Des Taffe and Michael Hilliar are another two silversmiths I have worked for. Michael is the creator of the famous History of Ireland range of jewellery. I worked with Des when he came to Alwrights with another silversmith and two polishers via Staunton’s, in a marriage arranged by Weir’s. Des would have been well acquainted with the Dunvegan Tea set and amazingly he was commissioned some years later

by the” Maguire” (the Chief of the Maguire clan) to make an exact replica of the Dunvegan Cup. The “Maguire” considered this cup to be a Chalice associated with the Maguire family and Des Taffe delivered the finished Chalice to the National Museum of Ireland in the last few years. Michael and Des both worked together when Weir’s reopened Matt Staunton’s old workshop on Dawson Street in 1972 under the name of Dublin Silver.

The silversmiths James Mary Kelly and Dessie Byrne were another two silversmiths I have had the pleasure of working with. I chased the Celtic knotwork on the two replicas of the Liam MacCarthy Cup for the G.A.A. This is the trophy presented to the winners of the All-Ireland Hurling Championship. It was a real treat to be involved in this work as the original was made by Edmond Johnson, of whose work I am a big fan. Ollie Ennis chased the first Sam Maguire for Des Byrne and I chased the most recent one. The Sam Maguire Cup is presented to the winners of the All-Ireland Gaelic Football Championship.

In 2005 the Dublin Assay Office commissioned me to follow my heart’s desire and make a piece for their collection. I chose to make a two foot high silver sculpture based on James Joyce’s masterpiece Ulysses. It’s in the form of a Moorish tower set in a bed of blooms. The two smaller towers on top of the main tower are decorated by flat chasing with my idea of Moorish interlacing and the main tower has eighteen chased and repoussed panels representing the 18 episodes of Ulysses spiraling up the Tower. Each panel is decorated with my take on the episode. James Joyce was a great fan of the Book of Kells and it inspired him in the writing of Ulysses.

In conclusion looking back I have had a very hit-and-miss career and would certainly not consider myself a role model for anyone, except maybe how not to do it. But having said all that I have had a very interesting and enjoyable time. My work has allowed me the privilege of meeting extremely talented and interesting people.

I have no intention of quitting the work I do and have ideas for making a few large pieces of silver. One of which is a vessel celebrating Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, the other is theTáin, featuring the exploits of CúChulainn.

FOLLOW ME ON FACEBOOK